Not everybody can travel to Antarctica for months at a time to study the continent’s unique ecology, flora and fauna.

Now two Northeastern University professors are among those calling for the establishment of an Antarctic biorepository to make sure that any serious researcher who wants to study the birds, animals, plants and microorganisms of the polar south gets a chance to do so.

According to Daniel Distel, director of the Ocean Genome Legacy Center, and H. William Detrich, professor emeritus at Northeastern’s Marine Science Center, the repository would help preserve a record of the rich biological diversity of the Southern Ocean and continent, which are uniquely susceptible to global warming.

The coldest place on earth, Antarctica is also the fastest warming, Distel says. He says researchers need access to biological samples from the area to learn “how global warming is affecting Antarctic species and to better understand how to protect them.”

“The biorepository will help democratize science, especially biological science,” Detrich says, adding, “There are many more scientists who want to study species in Antarctica than are able to actually get there.”

The Antarctic biorepository network would operate as a network from which people could borrow frozen tissue samples and dried biological specimens from collections across the U.S.

“People would be able to tap into a central database and find out where the materials are,” Distel says.

Detrich and Distel were among nearly two dozen scientists who contributed to a Dec. 8 commentary in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences calling for the National Science Foundation to fund an Antarctic biorepository network.

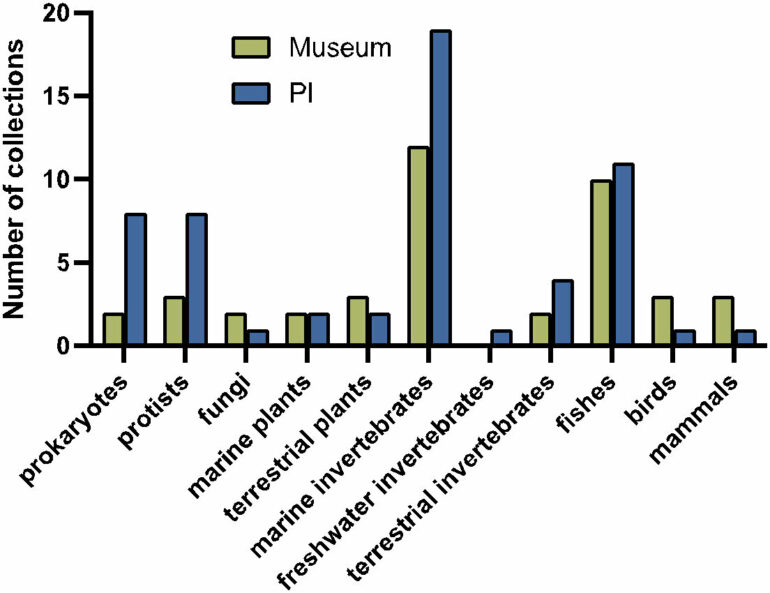

Currently, invaluable specimens are scattered across dozens of private collections and university laboratories. A few are also housed in museums.

Not only are the specimens hard to track down, Detrich says, they are in danger of being tossed when scientists retire.

In Detrich’s case, his freezer full of biological samples—collected on more than 20 expeditions to Antarctica—were saved from the waste heap when he and Distel got the idea to establish a polar genomics collection at the Ocean Genome Legacy Center of the Marine Science Center and Coastal Sustainability Institute in Nahant, Massachusetts.

“The U.S. Antarctic program has invested millions of dollars in my research program on the ice. Those millions of dollars are now in my freezer at Northeastern,” Detrich says.

The Ocean Genome Legacy Center now houses more than 30,000 marine DNA samples, not only from Detrich’s Antarctic explorations but also from the research of ocean scientists around the world.

Researchers already are able to borrow samples from OGL, but the establishment of a national Antarctic biorepository would make the lending process easier—and more uniform, Distel and Detrich say.

“Currently, researchers make their own collections and store their materials in their own way and store data in their own way,” Distel says. Uniform standards would make the lending process easier—and increase confidence in the reliability of specimens and data.

Distel says participants in a three-day virtual workshop in February convened by Kristin M. O’Brien of the University of Alaska in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic recognized that the lack of a biorepository was “an opportunity lost.”

“They realized that there was a vast resource out there that was not being adequately tapped,” Distel says. A white paper that came out of the workshop resulted in the PNAS opinion piece by O’Brien and Elizabeth L. Crockett of Ohio University to which Distel and Detrich also contributed.

As a subject of study, Antarctica is unique and holds important clues about the planet’s health.

The continent’s ice sheath is the largest on earth and contains 90% of the world’s ice in addition to 70% of its fresh water.

As the continent and its ocean warm faster than any other place on earth, the clock is ticking on opportunities to study its biodiversity, most of which consists of marine life, Distel and Detrich say.

“We need to be able to predict what kind of changes will occur to the biology of the ecosystem,” Detrich says.

“What kind of predictions can we make about the future of the food web in the Southern Ocean? Are some animals or phytoplankton more sensitive than others? If we have genomic resources, we can study these processes very closely, very carefully,” he says.

There is much to be discovered about life forms in Antarctica, Distel says.

“We know that there are threats facing all these organisms, but we haven’t completely cataloged what’s out there,” he says.

“A lot of what’s out there is still unknown, so there’s the risk of losing things before we’ve even learned they exist.”

Teaching responsibilities and lack of research funds keep many would-be Antarctic researchers—especially those who are young or from underrepresented communities—from studying the fauna of the polar south “on the ice,” as Detrich words it.

Detrich’s expeditions to Antarctica, which started in 1981, typically lasted from two to three months due to both the demands of his research and the limited window of time in which to travel by ship across unfrozen seas to his main base at Palmer Station.

“Palmer Station closes, going into winter operations, around the beginning of June and opens up again in early November,” which is the southern hemisphere’s spring, Detrich says.

Detrich knows full well the challenges of traveling to Antarctica.

On his last trip, in 2018, he suffered a fractured hip and pelvis when large waves hit the ice-hardened ship in which he was traveling and threw him out of his bunk bed.

The rest of the group, including a Northeastern co-op student, was able to complete the expedition, but Detrich had to be flown back to the U.S. for surgery.

“Getting across the Drake Passage is no easy matter,” Detrich says. “Most people get seasick.”

The establishment of an Antarctic biorepository network would mean that researchers who can’t—or don’t want to—travel to the continent could access anything from genomic data on mollusks and icefish to tissue plugs from living whales and penguins.

The next step, Distel says, is for O’Brien and Crockett to write a proposal for funding from the National Science Foundation to cover the costs of setting up software connecting the disparate collections, hiring coordinators and establishing a catalog and shipping protocols.

“Democratizing science and rescuing retiree collections are the two big ideas behind a biorepository,” Detrich says.

More information:

Kristin M. O’Brien et al, The time is right for an Antarctic biorepository network, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2212800119

Provided by

Northeastern University

Citation:

Why it’s crucial that scientists lend, not toss, specimens from Antarctica (2023, January 5)